Rejecting Behaviorism... Again.

This week [we seem to do this at the beginning of every semester in my field of study] we revisited the theoretical foundations of instructional design; a history steeped in dog drool and puctuated by the tap-tap-tap of a million tiny levers and the *clink* of food pellets dropping onto the floors of a million shiny metal cages. I suppose its a bit of an oversimplification to reduce all of behaviorism to those two rather poignant images, but only a bit. Every time we take this stroll down memory lane and I read things like this: "How do we present students with the right stimuli on which to focus their attention and mental effort so they will acquire important skills? That is the central problem of instruction." I find myself standing mentally agape, and probably more than a little judgmental.

"The central concern of instruction!?--maybe the central concern of dog-training, but certainly not the central concern of my interactions with another human being!" I think.

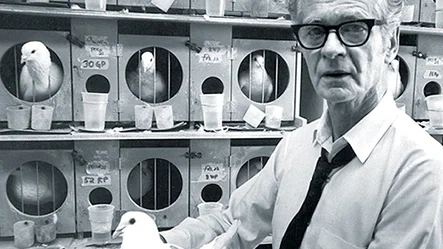

Reading Skinner's "Why We Need Teaching Machines" this semester probably didn't help that attitude.

- In arguing against the use of multiple-choice assessments [a position I whole-heartedly support, by the way] Skinner claims; "engaging in almost any of the ...behaviors which are the main concern of education, the student is to generate responses. He may generate and reject, but only rarely will be called on to generate a set of responses from which he must then make a choice." Is it just me or does that sound an awful lot like the process of creative problem-solving...arguably one of the most useful/valuable skills a student can gain from his/her education?!

- Skinner claims it is a simple yet profound misunderstanding that errors are essential or even beneficial to the learning process. "When material is carefully programmed," he claims "both subhuman and human subjects can learn while making few errors or none at all." Guess we better find some way to "carefully program" the real world so that these students who've learned without ever making a mistake don't end up suicidal inside a week.

- Finally, after describing a machine that would teach "subjects" to match correspondences of color, shape, sizes etc., Skinner affirms, "If devices similar to these were available in our nursery schools and kingergartens, our children would be fall more skillful in dealing with their environments. They would be more productive in their work, more sensitive to art and music, better at sports, and so on. They would lead more effective lives." Except, of course, for the minor detail that they would be socially dysfunctional automatons with little sense of their individual identity or agentive potential, let alone the creativity or confidence to engage it!

Whew.

At some point, often in the midst of a mental tirade, I am forced to admit that some really smart people believed this stuff, devoted their lives to it. And that these ideas contributed to critical advances in the way we conceptualize teaching and learning. And that someday in the not-too-terribly-distant future, someone may well be looking and the thoughts and theories I'm touting today and wondered how any sentient being could have convinced themselves the world worked that way.

In the final analysis, though, I'm still rejecting behaviorism...again.